----

Claudia Hausfeld

----

20.04 - 04.05 2013

----

Conversation about home and work, Bjarki Bragason & Claudia Hausfeld in April 2013:

BJARKI

When discussing your ideas for the exhibition I thought about the process one goes through when awarely or unawarely trying to access a partially buried or inaccessible past, like how you describe the returns to your home city after it has gone through massive changes, politically and otherwise; you go through processes or experiments to examine your relationship to the place. This is how I read the action of keeping photo diaries or your interest in comparing postcards of a city before and after its destruction, long after the event itself, after it has been turned into history.

Is this project a platform to think about what a home is, or could be?

CLAUDIA

Initially I was playing with the distortion of surfaces. I was interested in the destruction of houses as a sign of the passing of time. Houses are supposed to last a very long time, but in the end nothing lasts forever. Destruction and decay has always attracted me, but also frightened me a little bit. It reminds us of our own death. Then, by thinking about the matter more, I realized that I don’t have an anchor in the sense of place, a home country (heimat) or a childhood home that I could return to. Home is for me quite a blurry subject, it is not really connected to a place but to people or a story.

BJARKI

Buildings can remind us of the past. In places where sudden change has taken place, for example in the former East Block, they are also reminders of what has happened since what ever event we use as a turning point, often in the form that these buildings deteriorate, they get demolished or renovated. They become contested and politicized differently from before. They are a reminder of where we are now.

CLAUDIA

In that regard I find it very interesting what is going on in Berlin at the moment: The former culture palace of East Berlin, a huge concrete building with brown windows where I would watch theatre plays as a child, was torn down in order to make space for the rebuilding of the city palace that stood in its place before World War II. So an architectural reminder of the recent past is replaced by a dummy of a building that reaches back even further. The building that is going to be built is neither mirroring the “now” nor the “past”, it will be a mere theatrical backdrop to smoothen the view of the city.

BJARKI

Could you discuss the significance of using the form of the hut, this form of a small space, often associated with something which is temporary?

CLAUDIA

The hut is somehow a preliminary stage of a building. In buddhist pilgrimage, the pilgrim built a hut when he arrived at his designated spot, the holy place. The hut marked the end of his journey and the place where the temple was going to be built. The hut is the first primitive shelter and serves the localization, a sort of settling. For me, the hut represents the simplest form of shelter, but it also indicates the house or anything man-made that gives a place, or roots, to a person.

BJARKI

I was thinking about you clearing out your grandparents apartment the other day and what you said, that once this space has been emptied and is no longer within your reach, a big part of the material surroundings of your childhood will have become a memory. I suppose memory is not exclusively manifested in objects and things we have around us, but intimate spaces such as homes allow one to reflect on a time through space. You described taking photographs of the apartment and developing them only to find the film destroyed, blank. The symbolism of this is quite plain, regardless of how and why the film was blank.

CLAUDIA

For me, memory is very much connected to objects, or maybe just surface. Tangible things. They can be tangible with the eyes as well. I just remember that my grandmother, who had Dementia, would touch and feel anything she could get hold of with her hands, even when every other skill had left her. She couldn’t speak anymore and her world had reduced itself into whatever was in her reach. When I visited her the last time before she died, I was wearing a pullover that she had knitted. She was constantly touching and assessing it as if she recognized her work.

BJARKI

In an earlier conversation, you mentioned a longing to arrive. I understand this not as indulging in melancholy but rather as a search for what home is or can be. Once one has not lived in one’s country of birth for a long time, perhaps many of the homes which before could be visited no longer exist. You said that language is a place where you access the sensation of feeling at home. Can you discuss this, what role language has in your work? Also, juxtaposing situations, such as the collages, in which familiar urban settings appear in unfamiliar locations, such as in landscape?

CLAUDIA

Language, or mother tongue, is definitely a place to feel at home in. Being away, I use a language that I learned late and that I am not perfectly skilled in, so there are gaps, misunderstandings, unfinished thoughts. Sometimes I wonder how I come across using imperfect speech. I also make others use a language that they don’t usually use. It’s a bit of a double confusion. There is also the visual language which might be something that is formed before words and speech. I like confusion in visual language, seeing something that I haven’t seen before. It’s like learning a new language.

BJARKI

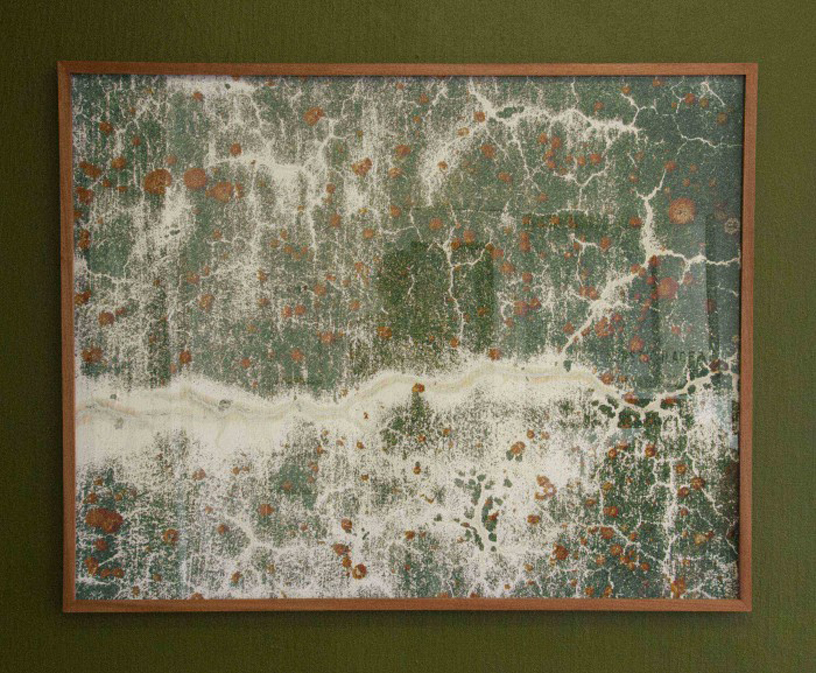

The corrugated iron in the centre of the space relates to the shapes of the huts in the photographs. It resonates with paper, a form of something which is discarded. Then there is the image of a facade that reminds of a map. I know you were thinking about obsolete maps before, can you talk about whether the iron and maps relate?

CLAUDIA

The surface of a house or a shelter is changed through time. It gets weathered, breaks or rusts. It can be an atlas of time, like the skin of an old person. Maps change constantly, too. All atlases from between 1949 and 1990 have the country I was born in printed in them. And probably many countries are not in them yet. With modern technology, these huge paper foldouts seem to be something from a remote past. I imagine the situation where you follow a GPS deep into some forest and then it stops working and you have no clue where you are because you never really confirmed a place. With a real map, one has to synchronize with the actual surrounding, one has to read the map and the place. A GPS makes this reading obsolete, the machine knows where you are.

BJARKI

Could you reflect on “Meðvirki Kofinn”, the codependent hut, and the relationship it forges with the clay hut also present?

CLAUDIA

The Co-dependant Hut is a structure that doesn’t exist without its surroundings. In a way that is probably true with everything, but buildings often carry a story that is not borrowed from the presence, like you mentioned above. Buildings always tell a story from within time, they don’t just reflect the now. Also buildings are not affected by outer circumstances as much as other things or people, they last comparably long in the shape they got assigned. The codependent hut is only a reflection of the “outside”, it has no story to tell. It is repellant and offers no shelter, it vanishes into it’s own surrounding. The clay hut on the other hand is without a surrounding. It is crumpled and worn and carries signs of force from the outside, but it doesn’t only reflect this force, it is formed through it. It tells a story and in that sense it is the opposite of the codependent hut, but it doesn’t offer shelter neither because it is solid.

----

----

Póstkort sýningarinnar

Postcard of the exhibition